The New Normal

Like it or not, the financial landscape is inextricably linked to environmental and social factors and the traditional balance sheet tells only part of the story. For decades, investors and analysts have focused on a company’s financial figures, treating factors like climate risk, labor practices, or brand reputation as “soft” or non-quantifiable. However, a seismic shift is underway. Businesses are increasingly recognizing that these non-financial issues can have a direct and significant impact on their bottom line.

This recognition has led to the rise of the materiality assessment—a fundamental process that helps companies identify and prioritize the most important environmental, social, and governance (ESG) topics to their business and their stakeholders. It is a strategic exercise that moves a company beyond generic sustainability initiatives to focus on what truly matters to its long-term financial performance and resilience. For financial professionals, understanding a company’s materiality assessment is like gaining access to a forward-looking risk register and a roadmap for future opportunities.

The Core Concept: Defining “Materiality”

At its heart, a materiality assessment is about relevance. The term “material” comes from accounting, where a factor is considered material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decisions of users of the financial statements. In the context of sustainability, this concept is broadened. A sustainability issue is material if it has the potential to significantly impact a company’s business model, strategy, financial performance, and value creation.

The process of conducting a materiality assessment typically involves three key steps:

- Identification: A company first compiles a comprehensive list of potential ESG issues relevant to its industry. This might include issues like carbon emissions, water consumption, human rights in the supply chain, data security, and employee health and safety.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Next, the company engages with its key stakeholders—including investors, customers, employees, suppliers, regulators, and local communities—to understand which of these issues are most important to them. This step is critical for gaining a 360-degree view and ensuring the assessment is not just an internal exercise.

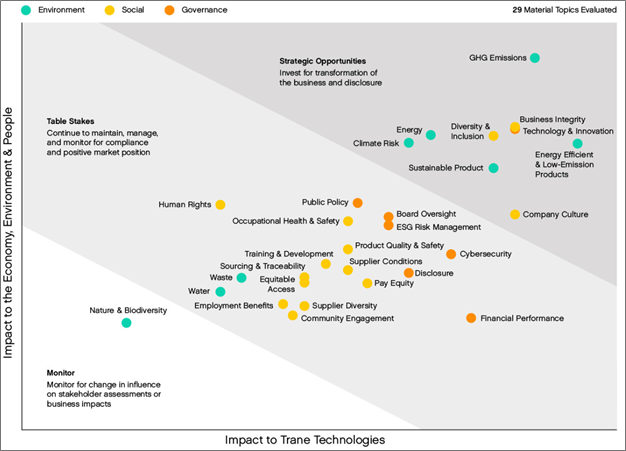

- Prioritization: The company then prioritizes these issues based on a two-dimensional matrix: their significance to the business (e.g., financial impact) and their significance to stakeholders. The issues that land in the top-right quadrant—those most important to both the business and its stakeholders—are considered “material.”

The output of this process is often a “materiality matrix,” a visual representation that guides a company on where to focus its sustainability efforts and reporting. Here’s an example of a materiality matrix, courtesy of Trane Industries, a global provider of heating and cooling solutions. Notice the most material topics are in the top-right corner.

The Evolving Framework: Financial vs. Impact Materiality

As the practice of materiality assessments has matured, a more sophisticated concept known as “double materiality” has emerged, particularly within the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This framework requires companies to consider two distinct perspectives:

- Financial Materiality: This perspective focuses on how sustainability issues create financial risks and opportunities for the company. For example, the risk of a new carbon tax, the opportunity to enter a green market, or the potential for increased operational costs due to water scarcity.

- Impact Materiality: This perspective focuses on how the company’s business activities impact people and the environment. This includes a company’s greenhouse gas emissions, its labor practices in the supply chain, or its impact on local communities.

The “double materiality” approach recognizes that a company’s impact on the world can, in turn, create a financial risk for the company itself. For example, a company’s impact on a local water source could lead to community backlash, regulatory fines, and reputational damage, all of which have direct financial consequences.

Examples of Material Non-Financial Factors and Their Financial Impact

Materiality assessments reveal that non-financial factors are not just abstract concepts; they are tangible drivers of financial performance. Here are some examples:

Environmental Factors

Climate Change

Financial Impact: Physical risks like extreme weather events (e.g., hurricanes, floods) can destroy physical assets and disrupt supply chains, leading to millions in damages and lost revenue.

Transition risks such as a carbon tax can directly increase a company’s operating costs. Conversely, a company that invests in renewable energy can lower its long-term energy costs and gain a competitive advantage.

Water Scarcity

Financial Impact: For industries like beverage production, agriculture, or semiconductor manufacturing, a lack of access to water can lead to production shutdowns, increased costs for water treatment, and fines for exceeding water usage limits, all of which directly impact profitability.

Waste and Pollution

Financial Impact: Poor waste management can result in regulatory fines, cleanup costs, and reputational harm. Conversely, investing in circular economy initiatives can reduce raw material costs and create new revenue streams from recycled products.

Social Factors

Climate Change

Financial Impact: Unsafe working conditions, unfair wages, or poor labor relations can lead to strikes, high employee turnover, reduced productivity, and legal fees from lawsuits. A company with a strong culture of employee well-being can benefit from lower recruitment costs and increased productivity.

Water Scarcity

Financial Impact: Data breaches can lead to massive fines (e.g., under GDPR), loss of customer trust, and remediation costs that can run into the hundreds of millions. A robust cybersecurity framework is a direct financial protector.

Waste and Pollution

Financial Impact: A company with a poor relationship with local communities can face protests, permitting delays, and operational interruptions, all of which translate to increased costs and project risk.

Governance Factors

Board Diversity

Financial Impact: A lack of diversity in the boardroom can lead to a narrow range of perspectives, groupthink, and a higher risk of poor strategic decisions. Research increasingly shows a link between board diversity and stronger financial performance.

Anti-Corruption Policies

Financial Impact: Weak anti-corruption measures can result in multi-million dollar fines, legal action, and a significant loss of investor confidence. Strong governance is a fundamental component of risk management and long-term stability.

From Assessment to Strategy: The Business Imperative

The results of a materiality assessment are not just for a sustainability report; they are a powerful tool for strategic planning. The insights gained help companies to:

- Allocate Capital: Direct investment towards projects that mitigate key risks or capitalize on sustainability-related opportunities.

- Enhance Risk Management: Integrate material ESG risks into enterprise-wide risk management frameworks.

- Improve Stakeholder Communication: Report on the issues that stakeholders care about most, building trust and strengthening relationships.

- Drive Innovation: Use material issues as a catalyst for developing new, more sustainable products and business models.

In conclusion, the traditional financial toolkit, while essential, is no longer sufficient on its own. A deep understanding of non-financial material factors and their financial implications is the new frontier for robust financial planning. By conducting a thorough materiality assessment, a company can transform potential vulnerabilities into a competitive advantage, creating long-term value that goes well beyond the numbers on a balance sheet.